Summers are easily the most professionally anticipated part of the year for an ecologist, and especially for a bird biologist who studies migratory birds. This summer has been a healthy mix of a month of frolicking through some beautiful forested landscape, nets and needles in tow, and alternating between lab-work and preparing to propose my Ph.D. dissertation research later this year.

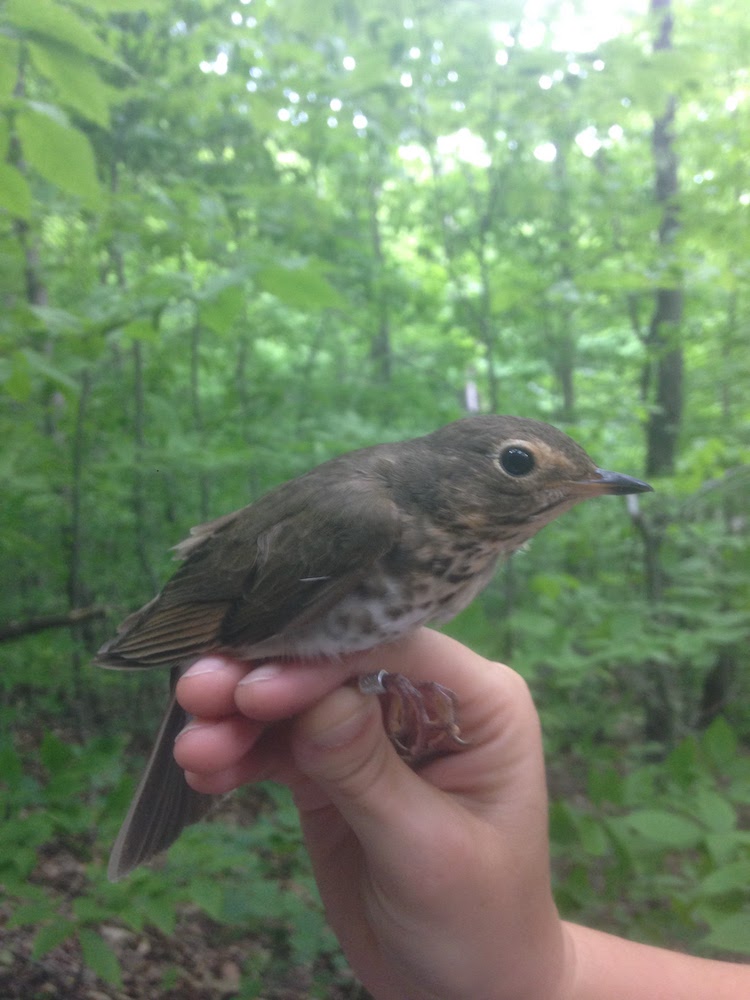

I study the diversity of malarial parasites in a group of birds that breed in North America, the Catharus thrushes, across different ecological gradients. Yes, you read that right, while the four malarial parasites that infect humans are restricted to more tropical climes, the thousands of malarial parasites that infect birds, other mammals and reptiles are found with a more global distribution.

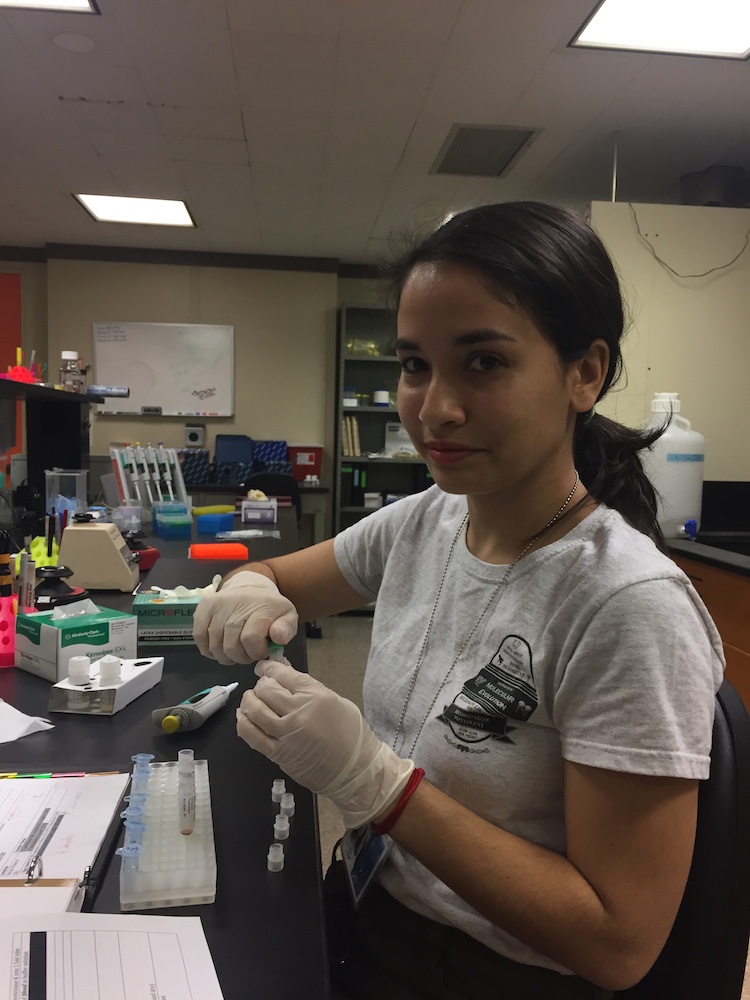

For the month of June, my research team of Eric (undergrad assistant), Alyssa (recent Ph.D. grad craving the last bit of bird field work before heading into the biology of fish) and I headed to the SUNY Newcomb campus in the Adirondack Mountains ready to catch lots of thrushes. We had certain minimum quotas for the three species that live in that field site, and despite the onslaught of mosquitos and blackflies, I’m proud to say we got higher than those quotas for all three species.

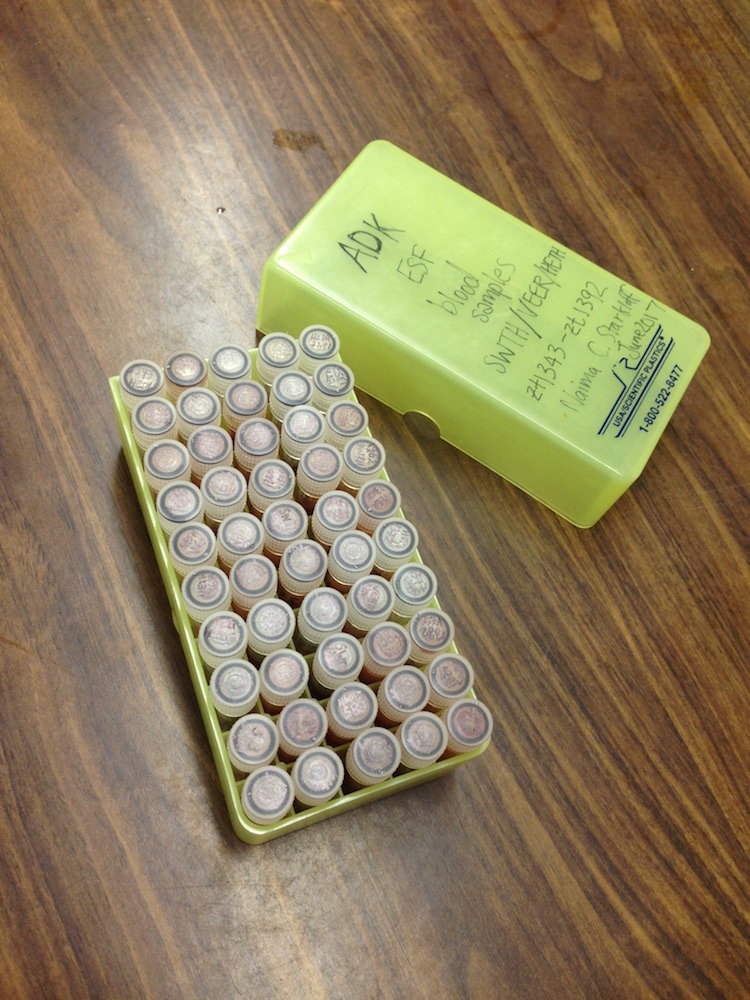

We catch birds using a technique called targeted mist-netting, where we put up a net along with a Bluetooth speaker, and play the bird’s call. The bird, suspecting a threat to its territory, will dash into the net. We very quickly remove it, and follow USGS protocols of measuring its dimensions and putting a metal band on its leg. Before releasing it, we take a very small blood sample (smaller than a raindrop), and preserve it in a buffer solution before adding it the New York State Museum’s archives.

Once back at the museum, we use genetic techniques to isolate a mitochondrial gene of any malaria parasite that may be floating around in the blood of the birds we caught. Once isolated, we can figure out what malaria species that specific genetic combination of mitochondrial gene it belongs to. And voila, we can make a catalog of malarial parasite diversity in my group of birds.