For folks in the bat community, field work generally means strenuous days and long nights, sometimes with little success in the post white-nose syndrome world. But when you catch the species you are looking for, especially one that has become extremely rare, it makes all the struggles worth it!

After working for the NYSDEC for the past few years I have become quite fond of these unique flying mammals, and after witnessing the results of the devastating fungal disease known as white-nose syndrome (WNS), I decided to pursue my own questions to contribute to these critical conservation efforts. Despite whether you love em or hate em, they are an ecologically important order of mammals that deserves much attention these days!

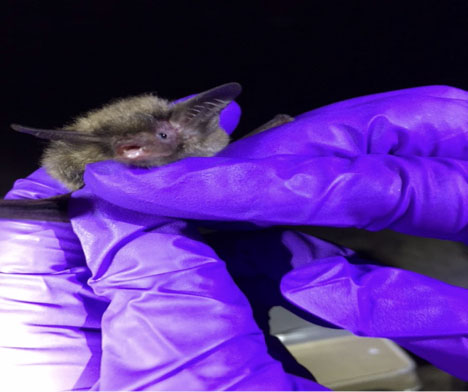

My study subject is the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis, or MYSE for short), a small brown bat of the eastern US. Despite the name, the ears are not quite as long as you might picture, however the tragus is the defining feature that sets this species apart from its Myotis counterparts by a much longer length! Unfortunately, MYSE have experienced a 99% population decline here in New York since the onset of WNS in 2006, and similar declines throughout the rest of their range. Over the past few years we have made some interesting observations here in NY, particularly that this species seems to be surviving down on Long Island, and this idea has been supported by other coastal regions of the country.

This spring involved lots of organization in order to narrow down my objectives and coordinate with other organizations so we can investigate the mechanisms promoting survival of coastal populations. One of the first things I wanted to look at was bats emerging from hibernation in the spring. At this time of the year, any surviving individuals should be heavily infected with the fungus, so determining whether our Long Island bats are even being exposed to the fungus was the first step. The problem is, if you have ever visited Long Island, you might realize that there are no natural hibernacula present! Bats typically use natural caves and abandoned mines, which there are none of, so this presents added difficulty in that we don’t know whether they are crossing back over to the mainland, or finding unique structures to spend the winter on the island.

Along with the DEC bat team, I headed down to do some mist netting in mid-April, selecting a location based on positive acoustic detections from the previous summer and guessing as to what the emergence period might be due to the weather and known ecology of the species at typical hibernaculum. I almost couldn’t believe my eyes when we caught 5 MYSE over two nights! That may not sound like a lot, but you could spend all summer netting in upstate NY and never catch a single one.

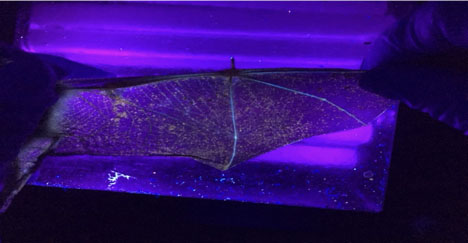

In order to test for exposure to the fungus causing the disease, Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd for short), we took swab samples of the wing and muzzle of each bat, which are then tested with qPCR for fungal presence and fungal load. Another quick tool for determining infection is to look for wing damage. Visually inspecting the wings can show some possible clues, but looking at the wings under UV light will actually show you lesions caused by the infection! In the picture above, you can see orange fluorescent dots on the wing, indicating this individual was exposed to the fungus. By taking photos of each wing, the amount of fluorescence can be quantified and used to assess severity of infection. After processing, each bat is released with a shiny forearm band in case of recapture at a later time. We were feeling pretty good after our successful trip south and looking forward to potentially returning to this site in the fall.